Jehan-Jacques Blancpain, the founder of the eponymous watch brand, was for sure an eclectic and busy man having worked as a breeder of horses and cattle, a school teacher, a watchmaker and, later in his life, as the mayor of Villeret, a municipality in the Jura administrative district in the canton of Bern in Switzerland.

Born in 1693 from a family of farmers, he officially started his watch business in 1735, transforming the upper floor of his farmhouse in a workshops. Horses and cattle were the guests of the ground floor.

Although 1735 is considered Blancpain’s foundation year, it is almost certain that the watchmaking activity started even earlier.

In fact, the reference to the 1735 year is based on a record of that year in an official property registry of the Villeret municipality where Jehan-Jacques Blancpain is indicated as “horloger”. It is reasonable to suppose that, before he could identify himself as a watchmaker, he must have been practicing the craft for some period before.

Nonetheless, setting the founding year in 1735 is still enough to establish Blancpain as the oldest watch company in the world having operated in continuity - in one form or another - from the official recording of Jehan-Jacques Blancpain as a watchmaker to the present day.

Jehan-Jacques had perceived the potential of the watchmaking business so, while he was still a school teacher, he began producing parts for pocket watches, then complete ebauche movements. By the second half of the century, complete watches were produced.

Jehan-Jacques was supported by his wife, most probably dedicated to polishing and decorating, and soon by his son Isaac - who, like his father, was also a school teacher - as well as by other relatives like uncles and aunts.

At the beginning of their activity, the Blancpains were not labelling their watches and preferred to sell their products without a trademark, a custom that was pretty common in the Villeret area at the time. This was unfortunate because, for this reason, today we do not have evidences of their pre-1800 work except for a Louis XVI pocket watch whose inner back is signed “Blancpain et fils”.

Isaac Blancpain did not follow his father Jehan-Jacques at the lead of the company. In fact, although he kept working at the workshop as a watchmaker, he preferred to focus on his main activity as a school teacher and leave this responsibility to his son David-Louis Blancpain (1765-1816), which demonstrated his skills and determination by traveling often through Europe, in particular to France and Germany, to sell and deliver Blancpain watches.

As a consequence of the French invasion of Switzerland and the Treaty of Campo Formio in 1797, Villeret was annexed to France. This had a very bad impact on the productivity of the company during the Napoleonic Wars (1803-1815) because all the young men of Villeret, including the Blancpains, became military conscripts. Nonetheless, Blancpain maintained a degree of continuity even during the wars.

After Napoleon's defeat and the Congress of Vienna, Villeret returned to Switzerland and was assigned to the Canton of Bern in 1815.

The lead of the company was now taken by Frédéric-Louis Blancpain, the eldest of the five sons of David-Louis. He transformed the work of the atelier introducing series methods and organizing production on an industrial basis with the use of machinery to increase productivity while optimizing quality.

He also developed ultra flat movements for his Lépine style watches (pocket watches featuring the crown at 12 o’clock with small seconds in line at 6 o’clock). Two centuries later, ultra flat movements are still very typical of Blancpain. By replacing the crown-wheel mechanism with a cylinder escapement, Frédéric-Louis introduced a major innovation into the watchmaking world.

Due to his bad health, Frédéric-Louis handed the company to his son, Frédéric-Emile, when he was just 19 years old.

To avoid confusion with his father, the young man decided to use only his middle name, so the company soon took the name of 'E. Blancpain’. Benefiting from the experience of his father, who despite his health worked alongside his son for 13 more years, Emile achieved remarkable success, building the business into the largest and most prosperous enterprise in Villeret.

Emile increased production by developing a modern assembly line, which divided tasks of the watchmakers into particular elements of the watches. The brand also distinguished itself as a specialist in the production of women’s watches, a specialty which is part of the DNA of the brand.

At the death of Frédéric-Emile in 1857, his sons Jules-Emile (born in 1832), Nestor and Paul-Alcide acquired the status of associates and the manufacture took the name of E. Blancpain & Fils' with Jules-Emile, who had acquired full watchmaking training in Switzerland and abroad, at the helm of the company.

To face the increasing price competition following the industrialization of companies worldwide, Blancpain built a two-storey factory by the Suze river in order to use hydraulic power to operate a generator and to supply electrical power to workshops and machinery.

By modernizing its methods and concentrating on top-of-range products featuring lever escapements, Blancpain become one of the few watchmaking firms to survive in Villeret in that challenging period.

In fact, of the 20 companies which existed when Jules-Emile and Paul-Alcide Blancpain took over the business, only three others apart from Blancpain were to survive through to the very early 1900s.

While Paul-Alcide decided to leave the company to pursue a career of all things brewing beer in Fribourg, Jules-Emile was joined by his son, Frédéric-Emile (not to be confused by his grandfather).

Frédéric-Emile continued the path of innovation of his father leading the Blancpain company until 1932.

For his later years, he was joined in 1915 by Betty Fiechter who assisted him in running the business. She joined the company as an apprentice when she was just 16 and soon her responsibilities at Blancpain grew quickly becoming head of manufacturing and commercial development. Frédéric-Emile had so much confidence in her skills and talent that he started training her for taking full responsibility of production and becoming the director of the company, a remarkable achievement for a woman at that time. We will write more about Betty in few paragraphs.

In the new century Blancpain kept expanding markets and also looked across the Atlantic, sending its marketing director, André Léal, over to the United States.

In 1926, the Manufacture entered into a partnership with John Harwood, a British watchmaker who had developed the first self-winding wristwatch (till then automatic winding systems only existed in pocket watches) obtaining a Swiss patent in 1924.

The new design placed a thick winding rotor off the end of the movement, allowing it to move back and forth in its channel over a 180 degree arc. To fight dust or water, the crown was removed and the watch featured a system for setting the time by rotating the bezel.

Unfortunately this type of automatic movement equipped with Harwood's rotor was not feasible to be housed in small ladies' watches. For this reason, Frédéric-Emile collaborated with the French watchmaker Leon Hatot to develop a different form of winding system which brought to the launch of the rectangular "Rolls", which became the world's first ladies' automatic watch.

Here the ingenious solution was to place the entire movement into a carriage that would allow it to slide back and forth, thereby recharging the mainspring. To facilitate the sliding, the watch was fitted with ball bearings between the movement and its carriage - hence the name of the new watch, the "Rolls".

On the sudden death of Frédéric-Emile Blancpain in 1932, his only daughter, Berthe-Nellie, did not wish to go into watchmaking. The following year, the two members of the staff who had been closest to Frédéric-Emile, Betty Fiechter and the sales director André Léal, bought the business.

A letter written by Frédéric-Emile's daughter, Nellie, to Betty Fiechter well explains the feelings of the persons involved in this delicate phase of the company:

“My dear Betty:

You can imagine that it is not without painful wrenching of my heart that I see the conclusion for me of the period that links me to all the memories of my childhood and youth. The end of Villeret for Papa brings real sadness, but I can assure you that the only solution which can truly ease my sadness is your taking over of the manufacture together with Mr Leal. Thanks to this fortunate solution I can see that the traditions of our precious past will he followed and respected in every way.

You were for Papa a rare and dear collaborator. One more time let me thank you for your great and lasting tenderness which I embrace and carry with me in my heart.

Best to you,

Nellie"

As there was no longer any member of the Blancpain family in control of the firm, the two associates were obliged by a Swiss law of the time to change the company name.

The firm would be called "Rayville S.A., successeur de Blancpain", "Rayville" being a phonetic anagram of Villeret. Despite this change of name, the identity of the Manufacture was perpetuated, and the characteristics of the brand were preserved.

With Betty Fiechter as the director, Blancpain had to face the effect of the Great Depression of the 1930s. One of the countermeasures was the opening to movement supply to other brands. In this period, Blancpain became a supplier of Gruen, Elgin and Hamilton, among the others.

The disappearance of Fiechter’s co-owner, André Léal, on the eve of World War II was another challenge for Betty. Nonetheless, in all these complex situations, Betty demonstrated that Frédéric-Emile was right in seeing her the new leader for Blancpain.

She was joined in 1950 by her nephew Jean-Jacques Fiechter which had a key role in the development of the Fifty Fathoms, the world’s first modern diving watch which debuted in 1953. The name was a reference to the depth rating of the watch (approximately 91.5 metres / 300 feet) expressed in fathoms. A fathom is a unit of length in the imperial and the U.S. customary systems equal to 1.8288 metres / 6 feet, used especially for measuring the depth of water.

Collaborating with the French combat divers, Jean-Jacques promoted its widespread adoption by navies around the world as well as its use by famous explorer Jacques Cousteau and his team.

To improve water resistance, Blancpain conceived a double sealed crown system to protect the watch from water penetration in the event that the crown were accidentally to be pulled during a dive. The presence of the second interior seal worked to guarantee the timepiece’s water tightness. A patent was registered for this invention.

A second patent was awarded for the sealing system for the caseback. This had indeed been a recurring problem with other pre-existing systems because the “O” ring, used to seal the caseback, could twist when the back was screwed into the case. In order to eliminate this risk, Fiechter invented a channel into which the “O” ring would be inserted and held in position by an additional metallic disk.

Fiechter then addressed another problem: a secured uni-directional rotating bezel that could be used to measure the time of a dive. Fiechter perfected a blocking mechanism which would prevent accidental rotation of the bezel. For this invention, he received a third patent.

Another huge success of the company was developed drawing upon a well-established Blancpain specialty, women’s timepieces.

The Fiechters wanted to create a landmark record setting watch: the smallest round watch for Ladies. Not just remarkable for its small size, the new watch had to be extremely robust. The Ladybird debuted in 1956 and become a worldwide hit.

From a technical point of view the Ladybird was characterized by two key innovations. The first was the addition of one extra wheel in the gear train. Normally a mechanical batch's wheel train consists of four wheels, counting the barrel drum as the first wheel and ending with the fourth which is driven by a pinion on the escapement. Fiechter's solution for reducing the size of the movement without compromising reliability was to add one more wheel. In fact, the fifth wheel helped to control the force arriving at the escapement, bringing robustness to the design. To avoid that the watch could run backwards because of the fifth wheel, the escapement was configured to run backwards.

The second innovation was the addition of anti-shock protection for the balance wheel. Preexisting extra-small movements, in the interest of size, omitted this critical element. As a consequence, these calibres were particularly fragile. Blancpain found a way to adapt anti-shock designs so that they could be fitted into the microsize of the Ladybird calibre.

As for the size, it was a record: 11.85 mm in diameter. Along with the record size for the movement overall was another record, the smallest balance wheel. So small, in fact, that Fiechter found that only the most skilled watchmakers could master its construction which required poising the smallest-in-the-world balance wheel with 22 minuscule gold screws.

The Ladybird enjoyed enormous commercial success both with watches sold under the name Blancpain and with watches sold under the name of different watch brands and jewelry houses. Square models were also developed.

By 1959 Rayville-Blancpain achieved a production level of more than 100,000 watches per year and the Fiechters realized that to support the continuous growth and fulfill demand while broadening marketing, more resources were needed.

The solution came in 1961 with a merger into the largest Swiss watch group of the time, the Société Suisse pour l’Industrie Horlogère (SSIH), joining Omega, Tissot and Lemania. Growth continued, new facilities were built and production soared to more than 220,000 pieces by 1971.

But serious big challenges came up in the 1970s. Not only the fall of the dollar against the Swiss franc reduced transatlantic exports and the first oil crisis triggered a world-wide recession but the entire Swiss watchmaking industry was seriously hit by the success of quartz watches from Japan (in fact, this period is often referred to as "the quartz crisis”) with dramatic sales drop.

As part of the reorganization, the new management of the Société Suisse pour l’Industrie Horlogère (SSIH) decided to build its strategy around quartz watches rather than mechanical ones, a decision which, in 1982, brought them to sell the Rayville-Blancpain name to a partnership of movement manufacturer Frédéric Piguet, led by Jacques Piguet, and Jean-Claude Biver, then an employee of SSIH.

The new company started trading under the name of Blancpain SA and set up production in an old building that had belonged for many generations to the Piguet family at Le Brassus, at an altitude of 1,000 meters in the Vallée de Joux.

Having studied attentively the company's history, Biver found out that Blancpain had never made quartz watches.

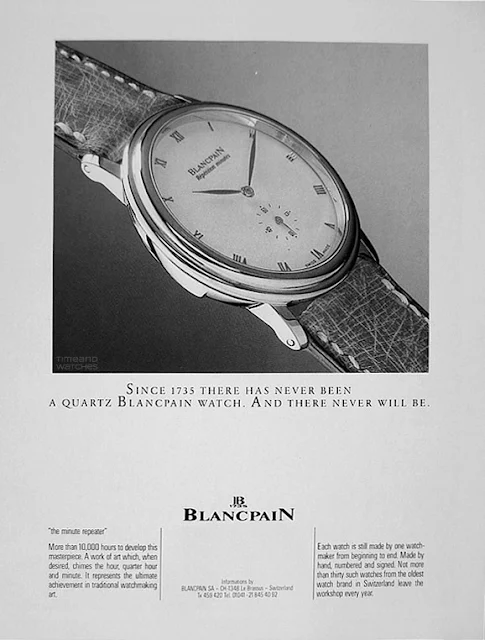

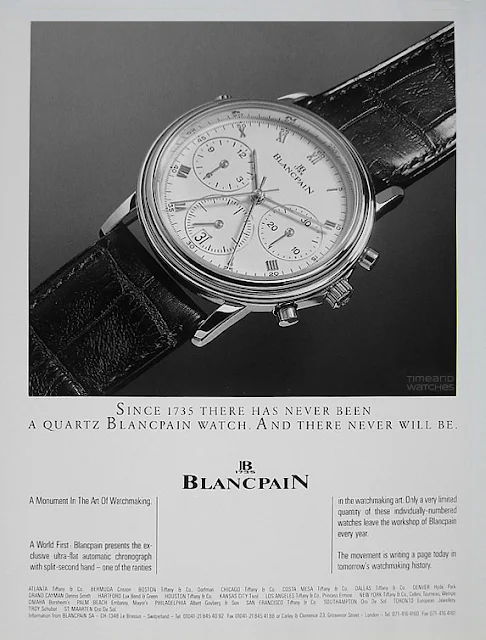

His simple strategy was summarized by the new slogan of the brand: "Since 1735, there has never been a quartz Blancpain watch. And there never will be."

Blancpain had to revive the cult of mechanical wristwatches producing classic mechanical watches in limited numbers, with an emphasis on complicated timepieces. And the company undoubtedly had a role in the revival of traditional mechanical watchmaking.

Its initial entry into the market was based on Calibre 6395, which established a record at the time as the smallest movement indicating the phases of the moon, day, month and date.

Presented for both women and men, the new watch combined separate windows for the display of the day of the week and the month, a dedicated date-hand, with days numbered on the outside perimeter of the dial, and a moon-phase window with the face on the moon, all strongly recalling the watchmaking heritage of the past.

In the following years the same round case was used for five other complications thus creating an outstanding suite of timepieces. After the complete calendar with moon phases, Blancpain added to its catalogue the perpetual calendar, the ultrathin, the minute repeater, the split-seconds chronograph and the tourbillon (although this should not be properly defined as a complication, rather a watchmaking feat).

In 1991, Blancpain presented the most complicated wristwatch in the world at the time: the 1735 Grande Complication. This exceptional timepiece featured a one-minute tourbillon regulator, a perpetual calendar with moon phases and moon age, a co-axial split seconds chronograph and a minute repeater activated by the slide on the band.

Requiring over ten months of work of a watchmaker master, the Blancpain 1735 Grande Complication was produced in just 30 pieces from 1991 to 2009, when the last example of the 30 left the factory.

In 1992, the Société Suisse pour l’Industrie Horlogère (SSIH) purchased Blancpain SA back for 60 million Swiss Francs (more than a thousand times the amount that was paid in 1983 for the brand name).

In this timeframe, SSIH and ASUAG - the two largest Swiss watch groups - merged in the Swiss Corporation for Microelectronics and Watchmaking Industries Ltd. (SMH) led by Nicolas G. Hayek who envisioned the restructuring. SMH was then renamed The Swatch Group in 1998.

In 1994, Blancpain launched the new series "2100" with new automatic movements offering 100 hours of power reserve. This line, oriented toward modern sportiness, was then renamed Leman and it is still today one of the key collections of the brand.

Jean-Claude Biver remained as CEO of the company until 2003 and was followed by Marc A. Hayek, the grandson of Swatch founder Nicolas.

The number of patent applications and world premieres grew significantly. New lines were also developed.

Among others, in 2008 Blancpain revived the Carrousel, a complication forgotten for over a century, and incorporated it into a wristwatch for the first time.

Villeret, Fifty Fathoms, Air Command, Ladybird, and Metiers d'Art are now the five collections which reflect Blancpain’s expertise and innovative strength.

Perpetuating its historical links with the oldest watchmaking tradition, Blancpain still makes its timepieces in the Jeux Valley, where Swiss clockmaking began, with its watchmakers and craftsmen distributed between Le Brassus and Le Sentier.

The former farmhouse in Le Brassus, lovingly restored and surrounded with forest and pastureland all around, helps master watchmakers in charge of the most prestigious and complicated timepieces to perform their precision work in a relaxed environment which helps concentration.

The site in Le Sentier is used by Blancpain for the brand’s R&D teams, as well as a number of workshops, after the incorporation of Frédéric Piguet SA - the sister company specialising in high-end movements - in 2010.

Blancpain remains faithful to its centuries-old heritage mastering each manufacturing phase and respecting Swiss watchmaking tradition.

At the same time, the brand keeps creating watches that innovate thanks to a constant focus to the improvement of the performance, accuracy and elegance of its timepieces. blancpain.com

By Alessandro Mazzardo. Latest revision on March 21, 2024

© Time and Watches. All Rights Reserved. Copying this material for use on other web sites or other digital and printed support without the written permission of Time and Watches or the copyright holder is illegal.

Born in 1693 from a family of farmers, he officially started his watch business in 1735, transforming the upper floor of his farmhouse in a workshops. Horses and cattle were the guests of the ground floor.

The Blancpain’s farmhouse. Originally serving as a mail relay station, it still stands today.

Although 1735 is considered Blancpain’s foundation year, it is almost certain that the watchmaking activity started even earlier.

In fact, the reference to the 1735 year is based on a record of that year in an official property registry of the Villeret municipality where Jehan-Jacques Blancpain is indicated as “horloger”. It is reasonable to suppose that, before he could identify himself as a watchmaker, he must have been practicing the craft for some period before.

Nonetheless, setting the founding year in 1735 is still enough to establish Blancpain as the oldest watch company in the world having operated in continuity - in one form or another - from the official recording of Jehan-Jacques Blancpain as a watchmaker to the present day.

Jehan-Jacques had perceived the potential of the watchmaking business so, while he was still a school teacher, he began producing parts for pocket watches, then complete ebauche movements. By the second half of the century, complete watches were produced.

A possible portrait of Jehan-Jacques Blancpain, though the identity is debated

Jehan-Jacques was supported by his wife, most probably dedicated to polishing and decorating, and soon by his son Isaac - who, like his father, was also a school teacher - as well as by other relatives like uncles and aunts.

At the beginning of their activity, the Blancpains were not labelling their watches and preferred to sell their products without a trademark, a custom that was pretty common in the Villeret area at the time. This was unfortunate because, for this reason, today we do not have evidences of their pre-1800 work except for a Louis XVI pocket watch whose inner back is signed “Blancpain et fils”.

Isaac Blancpain did not follow his father Jehan-Jacques at the lead of the company. In fact, although he kept working at the workshop as a watchmaker, he preferred to focus on his main activity as a school teacher and leave this responsibility to his son David-Louis Blancpain (1765-1816), which demonstrated his skills and determination by traveling often through Europe, in particular to France and Germany, to sell and deliver Blancpain watches.

As a consequence of the French invasion of Switzerland and the Treaty of Campo Formio in 1797, Villeret was annexed to France. This had a very bad impact on the productivity of the company during the Napoleonic Wars (1803-1815) because all the young men of Villeret, including the Blancpains, became military conscripts. Nonetheless, Blancpain maintained a degree of continuity even during the wars.

After Napoleon's defeat and the Congress of Vienna, Villeret returned to Switzerland and was assigned to the Canton of Bern in 1815.

The lead of the company was now taken by Frédéric-Louis Blancpain, the eldest of the five sons of David-Louis. He transformed the work of the atelier introducing series methods and organizing production on an industrial basis with the use of machinery to increase productivity while optimizing quality.

He also developed ultra flat movements for his Lépine style watches (pocket watches featuring the crown at 12 o’clock with small seconds in line at 6 o’clock). Two centuries later, ultra flat movements are still very typical of Blancpain. By replacing the crown-wheel mechanism with a cylinder escapement, Frédéric-Louis introduced a major innovation into the watchmaking world.

Blancpain pocket watch with cylinder escapement

Due to his bad health, Frédéric-Louis handed the company to his son, Frédéric-Emile, when he was just 19 years old.

To avoid confusion with his father, the young man decided to use only his middle name, so the company soon took the name of 'E. Blancpain’. Benefiting from the experience of his father, who despite his health worked alongside his son for 13 more years, Emile achieved remarkable success, building the business into the largest and most prosperous enterprise in Villeret.

The village of Villeret and, below, the Blancpain's workshops - circa 1860

At the death of Frédéric-Emile in 1857, his sons Jules-Emile (born in 1832), Nestor and Paul-Alcide acquired the status of associates and the manufacture took the name of E. Blancpain & Fils' with Jules-Emile, who had acquired full watchmaking training in Switzerland and abroad, at the helm of the company.

To face the increasing price competition following the industrialization of companies worldwide, Blancpain built a two-storey factory by the Suze river in order to use hydraulic power to operate a generator and to supply electrical power to workshops and machinery.

By modernizing its methods and concentrating on top-of-range products featuring lever escapements, Blancpain become one of the few watchmaking firms to survive in Villeret in that challenging period.

In fact, of the 20 companies which existed when Jules-Emile and Paul-Alcide Blancpain took over the business, only three others apart from Blancpain were to survive through to the very early 1900s.

The Blancpain workshops in Villeret in the 1920s

Frédéric-Emile continued the path of innovation of his father leading the Blancpain company until 1932.

Frédéric-Emile Blancpain

For his later years, he was joined in 1915 by Betty Fiechter who assisted him in running the business. She joined the company as an apprentice when she was just 16 and soon her responsibilities at Blancpain grew quickly becoming head of manufacturing and commercial development. Frédéric-Emile had so much confidence in her skills and talent that he started training her for taking full responsibility of production and becoming the director of the company, a remarkable achievement for a woman at that time. We will write more about Betty in few paragraphs.

In the new century Blancpain kept expanding markets and also looked across the Atlantic, sending its marketing director, André Léal, over to the United States.

In 1926, the Manufacture entered into a partnership with John Harwood, a British watchmaker who had developed the first self-winding wristwatch (till then automatic winding systems only existed in pocket watches) obtaining a Swiss patent in 1924.

The new design placed a thick winding rotor off the end of the movement, allowing it to move back and forth in its channel over a 180 degree arc. To fight dust or water, the crown was removed and the watch featured a system for setting the time by rotating the bezel.

The Harwood automatic watch based on Blancpain movements featuring the automatic winding systems invented by the British watchmaker

Unfortunately this type of automatic movement equipped with Harwood's rotor was not feasible to be housed in small ladies' watches. For this reason, Frédéric-Emile collaborated with the French watchmaker Leon Hatot to develop a different form of winding system which brought to the launch of the rectangular "Rolls", which became the world's first ladies' automatic watch.

The Rolls

Here the ingenious solution was to place the entire movement into a carriage that would allow it to slide back and forth, thereby recharging the mainspring. To facilitate the sliding, the watch was fitted with ball bearings between the movement and its carriage - hence the name of the new watch, the "Rolls".

On the sudden death of Frédéric-Emile Blancpain in 1932, his only daughter, Berthe-Nellie, did not wish to go into watchmaking. The following year, the two members of the staff who had been closest to Frédéric-Emile, Betty Fiechter and the sales director André Léal, bought the business.

A letter written by Frédéric-Emile's daughter, Nellie, to Betty Fiechter well explains the feelings of the persons involved in this delicate phase of the company:

“My dear Betty:

You can imagine that it is not without painful wrenching of my heart that I see the conclusion for me of the period that links me to all the memories of my childhood and youth. The end of Villeret for Papa brings real sadness, but I can assure you that the only solution which can truly ease my sadness is your taking over of the manufacture together with Mr Leal. Thanks to this fortunate solution I can see that the traditions of our precious past will he followed and respected in every way.

You were for Papa a rare and dear collaborator. One more time let me thank you for your great and lasting tenderness which I embrace and carry with me in my heart.

Best to you,

Nellie"

As there was no longer any member of the Blancpain family in control of the firm, the two associates were obliged by a Swiss law of the time to change the company name.

The firm would be called "Rayville S.A., successeur de Blancpain", "Rayville" being a phonetic anagram of Villeret. Despite this change of name, the identity of the Manufacture was perpetuated, and the characteristics of the brand were preserved.

With Betty Fiechter as the director, Blancpain had to face the effect of the Great Depression of the 1930s. One of the countermeasures was the opening to movement supply to other brands. In this period, Blancpain became a supplier of Gruen, Elgin and Hamilton, among the others.

The disappearance of Fiechter’s co-owner, André Léal, on the eve of World War II was another challenge for Betty. Nonetheless, in all these complex situations, Betty demonstrated that Frédéric-Emile was right in seeing her the new leader for Blancpain.

Betty Fiechter and her nephew Jean-Jacques Fiechter

Above and below, the original Fifty Fathoms diver's watch - 1953

Collaborating with the French combat divers, Jean-Jacques promoted its widespread adoption by navies around the world as well as its use by famous explorer Jacques Cousteau and his team.

To improve water resistance, Blancpain conceived a double sealed crown system to protect the watch from water penetration in the event that the crown were accidentally to be pulled during a dive. The presence of the second interior seal worked to guarantee the timepiece’s water tightness. A patent was registered for this invention.

Vintage advertisement of the Fifty Fathoms

Extract from the U.S. patent granted to Blancpain for the case of the Fifty Fathoms in 1959. The watch was granted two more patents: for the double sealed crown and for the rotating locking bezel.

Fiechter then addressed another problem: a secured uni-directional rotating bezel that could be used to measure the time of a dive. Fiechter perfected a blocking mechanism which would prevent accidental rotation of the bezel. For this invention, he received a third patent.

The Fifty Fathoms played an essential role in the development of scuba diving and the discovery of the ocean world becoming one of the most iconic diver's watch ever designed, the one that set the benchmark for diver's watches. To read about all the key milestones of this timepiece, you can read our in-depth article "The history of the Blancpain Fifty Fathoms".

Another huge success of the company was developed drawing upon a well-established Blancpain specialty, women’s timepieces.

The Fiechters wanted to create a landmark record setting watch: the smallest round watch for Ladies. Not just remarkable for its small size, the new watch had to be extremely robust. The Ladybird debuted in 1956 and become a worldwide hit.

From a technical point of view the Ladybird was characterized by two key innovations. The first was the addition of one extra wheel in the gear train. Normally a mechanical batch's wheel train consists of four wheels, counting the barrel drum as the first wheel and ending with the fourth which is driven by a pinion on the escapement. Fiechter's solution for reducing the size of the movement without compromising reliability was to add one more wheel. In fact, the fifth wheel helped to control the force arriving at the escapement, bringing robustness to the design. To avoid that the watch could run backwards because of the fifth wheel, the escapement was configured to run backwards.

Ladybird models

As for the size, it was a record: 11.85 mm in diameter. Along with the record size for the movement overall was another record, the smallest balance wheel. So small, in fact, that Fiechter found that only the most skilled watchmakers could master its construction which required poising the smallest-in-the-world balance wheel with 22 minuscule gold screws.

Vintage advertisement presenting the Ladybird as the smallest mechanical round watch with a diameter of just 11.85 mm

The Ladybird enjoyed enormous commercial success both with watches sold under the name Blancpain and with watches sold under the name of different watch brands and jewelry houses. Square models were also developed.

The rectangular gem-set Blancpain Ladybird owned by Marilyn Monroe. Adorned with 71 round diamonds and two marquise diamonds, it was bought back by Blancpain SA at an auction held by Julien's Auctions in 2016 for the amount of US$ 225,000 to become part of Blancpain's permanent Museum collection.

By 1959 Rayville-Blancpain achieved a production level of more than 100,000 watches per year and the Fiechters realized that to support the continuous growth and fulfill demand while broadening marketing, more resources were needed.

The Rayville Blancpain building in Villeret - 1963

The solution came in 1961 with a merger into the largest Swiss watch group of the time, the Société Suisse pour l’Industrie Horlogère (SSIH), joining Omega, Tissot and Lemania. Growth continued, new facilities were built and production soared to more than 220,000 pieces by 1971.

But serious big challenges came up in the 1970s. Not only the fall of the dollar against the Swiss franc reduced transatlantic exports and the first oil crisis triggered a world-wide recession but the entire Swiss watchmaking industry was seriously hit by the success of quartz watches from Japan (in fact, this period is often referred to as "the quartz crisis”) with dramatic sales drop.

As part of the reorganization, the new management of the Société Suisse pour l’Industrie Horlogère (SSIH) decided to build its strategy around quartz watches rather than mechanical ones, a decision which, in 1982, brought them to sell the Rayville-Blancpain name to a partnership of movement manufacturer Frédéric Piguet, led by Jacques Piguet, and Jean-Claude Biver, then an employee of SSIH.

The new company started trading under the name of Blancpain SA and set up production in an old building that had belonged for many generations to the Piguet family at Le Brassus, at an altitude of 1,000 meters in the Vallée de Joux.

Having studied attentively the company's history, Biver found out that Blancpain had never made quartz watches.

His simple strategy was summarized by the new slogan of the brand: "Since 1735, there has never been a quartz Blancpain watch. And there never will be."

Blancpain had to revive the cult of mechanical wristwatches producing classic mechanical watches in limited numbers, with an emphasis on complicated timepieces. And the company undoubtedly had a role in the revival of traditional mechanical watchmaking.

Its initial entry into the market was based on Calibre 6395, which established a record at the time as the smallest movement indicating the phases of the moon, day, month and date.

The Blancpain complete calendar moon-phase watches and their Calibre 6395 (below)

Presented for both women and men, the new watch combined separate windows for the display of the day of the week and the month, a dedicated date-hand, with days numbered on the outside perimeter of the dial, and a moon-phase window with the face on the moon, all strongly recalling the watchmaking heritage of the past.

In the following years the same round case was used for five other complications thus creating an outstanding suite of timepieces. After the complete calendar with moon phases, Blancpain added to its catalogue the perpetual calendar, the ultrathin, the minute repeater, the split-seconds chronograph and the tourbillon (although this should not be properly defined as a complication, rather a watchmaking feat).

Advertising for the Minute Repeater - 1989

Advertising for the ultra-flat automatic chronograph with split seconds - 1990

Requiring over ten months of work of a watchmaker master, the Blancpain 1735 Grande Complication was produced in just 30 pieces from 1991 to 2009, when the last example of the 30 left the factory.

Above and below, the Blancpain 1735 and its movement

In this timeframe, SSIH and ASUAG - the two largest Swiss watch groups - merged in the Swiss Corporation for Microelectronics and Watchmaking Industries Ltd. (SMH) led by Nicolas G. Hayek who envisioned the restructuring. SMH was then renamed The Swatch Group in 1998.

In 1994, Blancpain launched the new series "2100" with new automatic movements offering 100 hours of power reserve. This line, oriented toward modern sportiness, was then renamed Leman and it is still today one of the key collections of the brand.

The automatic chronograph Leman Flyback 2185 became a classic both for its design and for its exclusive manufacture movement

Jean-Claude Biver remained as CEO of the company until 2003 and was followed by Marc A. Hayek, the grandson of Swatch founder Nicolas.

Mark A. Hayek (on the right) with Jean-Jacques Fiechter in 2013

The number of patent applications and world premieres grew significantly. New lines were also developed.

Among others, in 2008 Blancpain revived the Carrousel, a complication forgotten for over a century, and incorporated it into a wristwatch for the first time.

The Blancpain Carrousel Volant featuring a one minute flying carrousel

Villeret, Fifty Fathoms, Air Command, Ladybird, and Metiers d'Art are now the five collections which reflect Blancpain’s expertise and innovative strength.

Perpetuating its historical links with the oldest watchmaking tradition, Blancpain still makes its timepieces in the Jeux Valley, where Swiss clockmaking began, with its watchmakers and craftsmen distributed between Le Brassus and Le Sentier.

The former farmhouse in Le Brassus, lovingly restored and surrounded with forest and pastureland all around, helps master watchmakers in charge of the most prestigious and complicated timepieces to perform their precision work in a relaxed environment which helps concentration.

The site in Le Sentier is used by Blancpain for the brand’s R&D teams, as well as a number of workshops, after the incorporation of Frédéric Piguet SA - the sister company specialising in high-end movements - in 2010.

Blancpain remains faithful to its centuries-old heritage mastering each manufacturing phase and respecting Swiss watchmaking tradition.

At the same time, the brand keeps creating watches that innovate thanks to a constant focus to the improvement of the performance, accuracy and elegance of its timepieces. blancpain.com

By Alessandro Mazzardo. Latest revision on March 21, 2024

© Time and Watches. All Rights Reserved. Copying this material for use on other web sites or other digital and printed support without the written permission of Time and Watches or the copyright holder is illegal.