The Leap Year in the A. Lange & Söhne perpetual calendars. Today is a leap day, the 29th of February that only occurs about every 4 years to keep our calendars in alignment with the Earth and the sun.

Today is a leap day, the 29th of February that only occurs about every 4 years to keep our calendars in alignment with the Earth and the sun.

We need leap days because it takes 365.2422 days for our planet to complete one revolution around the sun. Thus, the actual orbit is a quarter of a day longer than our 365-day year. Of course, we cannot add quarter days to each year so it was decided to add a leap day every four years.

In watchmaking, only perpetual calendars correctly reproduces the transition from 28 to 29 February, and subsequently switches directly to 1 March at midnight of the leap day. With annual calendars, you have to manually set the date once per year, at the end of February.

While this difference might sound a small thing, it is a real technical challenge. In fact, it requires the development of a mechanical programme that maps the different durations of all 48 months across the entire four-year cycle.

Usually, this complication is handled by a programme wheel with 48 notches and steps, which correspond to the different durations of the 48 months in the four-year cycle of three regular years and a leap year. This is also the type of mechanism adopted by A. Lange & Söhne for seven of its eight timepieces featuring a perpetual calendar.

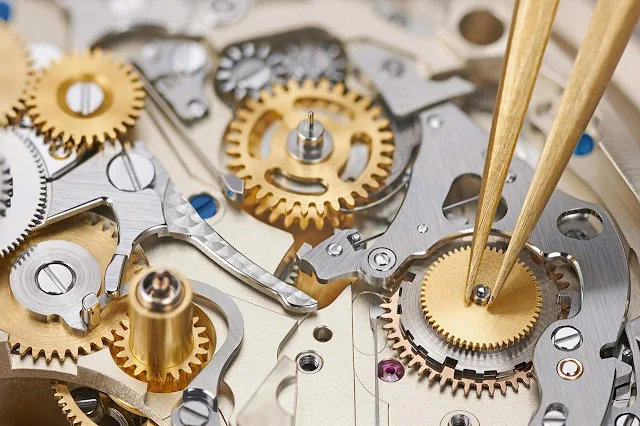

Above and below, the Tourbograph Perpetual “Pour le Mérite” (calibre L133.1); the bearing of the programme wheel is being lubricated with oil. It goes around once in four years and contains the information as to the different lengths of the 48 months in the four-year cycle.

This one marks the February of the leap year with an additional calendar day. The mechanism recognises the different lengths of the months for an entire century. A correction is only necessary in the secular years 2100, 2200 and 2300, which according to the Gregorian calendar will not be leap years.

Above and below, the Datograph Perpetual Tourbillon (calibre L952.2); the leap-year disc is held in its position by a hold-down device fixed with a screw.

However, for its Lange 1 Tourbillon Perpetual Calendar, launched in 2012, the Saxon watchmaker used a completely new approach.

The Lange 1 Tourbillon Perpetual Calendar housing the calibre L082.1

Its key element is a patented peripheral month ring, which constituted an entirely new type of month display. It replaces the traditional mechanism in which the month is advanced by a notched programme wheel. The solution was devised in order to harmoniously integrate the multitude of calendar indications into the dial architecture of the Lange 1 without affecting the asymmetric arrangement of non-overlapping displays (more on the Lange 1 and its history can be found here).

Lange 1 Tourbillon Perpetual Calendar (calibre L082.1); assembly of the leap-year indication. The numeral disc is positioned on top of the leap-year arbour.

In this exclusive model the month ring is driven via its internal gearing. It rotates around its own axis once a year. The inside of the gear rim features a circumferential contour with wavy recesses. A spring-loaded sampler lever glides along this contour and is deflected by a magnitude that corresponds to the depth of the respective recess.

The more it is deflected, the shorter the month. In February, an extender of the sampler lever contacts a cam beneath the leap-year disc. This tells the mechanism whether it is a common year with only 28 days in February or a leap year with 29 days.

Innovating in a perpetual calendar mechanism is tough but still possible. alange-soehne.com

COMMENTS